The Vector Expedited Review Voucher (VERV), modelled on the already established US Priority Review Voucher (PRV) for drug development, is a proposed no cost new incentive to encourage R&D focussed agriculture companies to innovate in public health where there are significant economic barriers to product innovation. The VERV would encourage companies to invest in novel insecticide development for public health, such as malaria, by rewarding the registrant of a new public health insecticide with a voucher to receive an expedited review of a second, more profitable product outside public health. Getting to market faster is valuable and gives an innovator registrant an opportunity to generate a financial return to mitigate the development cost losses on a public health use insecticide.

Personal Experiences with Malaria 23rd April 2021A Little About Me

I was born and raised in Cameroon, which is a malaria endemic country. My experiences growing up led me to want to work in the malaria field, I studied biochemistry planning to build a career in malaria research. However, after studies I instead joined the pharmaceutical industry working on accelerating access to malaria medicines. Today, I am very privileged to be working in vector control, which gives me a holistic understanding of the challenges to malaria eradication and a chance to impact the fight against the disease from a different angle.

My Experiences with Malaria

I grew up in a Sahelian area in the north of Cameroon close to Chad in the 1980’s. The climate there is typically hot, sunny, dry and somewhat windy all year long. Malaria was seasonal and I remember taking chloroquine tablets on a weekly basis as prophylaxis during the high transmission season, typically the raining season. At that time rapid diagnostic tests were not common and every fever would have been treated first as malaria.

After my studies, I moved in the south of the country closer to the equator. Here the climate was completely different, it is an equatorial climate hot and wet all year round. The annual rainfall is high as it rains almost every day and this creates a humid climate, which is an ideal set up for mosquitoes. Indeed, in the south of Cameroon malaria is endemic and the probability of being infected is very high throughout the year. . It was a typical high burden area. Following this move, my relationship with malaria definitely changed after getting malaria for the first time in more than a decade almost immediately.

To make things worse, I neglected the symptoms as they showed up during a business trip in Morocco far from home. Fortunately, I was able to access to a treatment quickly and recovered without any complication. Having a malaria episode out of an endemic country has sometimes been a real challenge for people, many people died because of misdiagnosis and delayed care. Indeed, treating malaria early is the best way to handle the disease when the care is delayed it can lead to serious complications.

After that first malaria experience as an adult, I started being more conscious of vector control. I didn’t want to get sick again and prevention is key to this. I started using insecticide sprayers and I would spray my bedroom everyday before going to sleep. Despite these precautions I experienced in general one malaria episode per year. I started using bed nets routinely when my daughter was born. I was able to buy one in a shop, on the private market. She slept under a bed net every night. Throughout the years, my experience of malaria has evolved, based on where I where I lived (Sahel or equatorial climate), my age and status (mother). Having more information about the options available to me to prevent malaria and protect my family was so important.

What Next in Eradication?

There is a real opportunity to eradicate malaria in maximizing efforts in high burden set ups, communities are fighting the disease on daily basis and just need the appropriate tools and empowerment to defeat it. A lot still needs to be done to teach the about the disease at a very early age, to ensure better awareness of symptoms and good practices to prevent and treat the disease early. Engaging the youth and supporting alternative route to market could be very robust initiatives in tackling the disease. Finally, I definitely became more alert on the disease and proactive when I became a mother. To defeat malaria, we should find a way to partner more with women in communities, they often face the largest burdens of malaria (during their pregnancy and as caregivers) and hold a lot of decision making power. Raising their awareness and collaborating with them in the design and implementation of the new tools in the IVCC pipeline will allow for equitable and quicker adoption of life saving interventions.

New Routes to Market 8th April 2021The introduction of new vector control technologies is critical to supporting insecticide resistance management (IRM) and progressing towards the elimination of malaria. However, these new tools including 3rd generation insecticides for indoor residual spraying (IRS) and dual-active ingredient mosquito nets are more expensive than existing tools and will be difficult to introduce without reducing coverage as malaria budgets have plateaued and are under further pressure due to the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

With this in mind IVCC is working on a range of market shaping interventions to increase affordability and expand coverage, including a “New Routes to Market” initiative. IVCC is working with a handful of High Burden High Impact (HBHI) countries including DRC, Ghana, Nigeria and Uganda to explore the potential of expanding coverage beyond the constraints of current donor funding through public private partnerships based on successful work done with mining companies, mission hospitals and NGOs under the Next Generation IRS project (NgenIRS). Although these new distribution networks will be initially set up to expand IRS coverage, they will ultimately be available for the distribution of other vector control tools based on the specific needs of partner countries.

Although in the early stages, countries have expressed great interest and have begun the process, with IVCC’s support, to identify and engage private sector funding and implementation partners. To this end a private sector roundtable was organised by the Ghanaian National Malaria Program as part of the Zero Malaria Starts with Me campaign. The roundtable brought together over 80 private companies to discuss the pressing need for their involvement in the fight against malaria. In Nigeria a similar roundtable hosted by GBCHealth’s Corporate Alliance on Malaria in Africa and the National Malaria Elimination Programme (NMEP) brought together over 155 participants including speakers from government, industry, academia and civil society to deliberate on ways to maximise impact on malaria vector control interventions in Nigeria. Other private sector roundtables will be planned in other partner countries in the coming months with the hope of identifying partners that can expand IRS coverage within the next year.

The Role of Surface Type in IRS 22nd October 2020This blog post is a guest blog from Aimee-Louise Whalley who is undertaking a MSc at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine.

After completing my undergraduate degree, I was a little lost and unsure of what was next! I had worked and travelled but found myself eager to study biology again, in a field that made a huge difference to people’s lives. During my master’s degree in Tropical Disease Biology at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) I developed an interest in vector control and chose to carry out my research project with IVCC. The project was investigating the role of surface type in Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS).

In 2018, there were 228 million cases of malaria globally, 405,000 of which resulted in death. Despite increasing our knowledge and advancements in technology for combatting malaria, and other vector-borne diseases, new control tools must be developed, and existing tools must be improved if we want to reach eradication. IRS is one such control tool, which involves the coating of internal walls and other surfaces with a residual insecticide. Previous studies have shown variation in IRS performance across sprayed surface types, with suggestions that porous surfaces like mud and dung are particularly poor for insecticide persistence. Mud is a common housing material in sub-Saharan Africa, where malaria is most present. If the role of surface type is understood further and investment is made into overcoming the challenges IRS faces, more effective IRS application can be achieved. This could result in prevented disease and lives saved.

The initial idea for my MSc project was to conduct bioassays on mud brick samples taken from several countries across Africa. This would help identify the physicochemical properties that may be responsible for the residual efficacy of sprayed insecticide on the different muds. As the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted all of our lives, laboratory research plans were halted, and the scope of the research had to change. During my project I conducted a review of the literature, to summarise the existing knowledge on the differences in residual efficacy seen between common surface types (for example dung, mud, cement, wood and paint), and on surface-insecticide interactions that influence residual efficacy. Following that, I looked at three IVCC laboratory data sets to observe any variability in residual efficacy between and within surface types. The results found that porous surfaces like mud and dung surfaces showed the shortest and most varied residual efficacies compared to less porous surfaces like wood and paint.

Mud varies in composition and can vary across geographical location. The physicochemical analysis of seven mud brick samples across geographies were used to identify the properties that influence insecticide persistence. A positive correlation was seen with increasing mud porosity and short insecticide residual efficacy. This research provides preliminary findings from which can be built upon in future laboratory research, which would lead to a better understand of the interactions between surfaces and insecticides. I have highlighted that surface type does play a significant role in IRS performance and must be considered throughout the development of new IRS products. This is key to understanding how effective new IRS products entering the market will be. This should include testing new products on different surface types in the development stage and collaborating with stakeholders to develop innovative ways to improve the residuality of IRS products on challenging surfaces, particularly mud.

From my experience with IVCC and LSTM I feel fortunate to have gained an insight into the workings of a Product Development Partnership and how stakeholder collaborations allow for sustainable research and development. I was given the independence to develop my own research on this topic, with guidance and support from Dr Derric Nimmo, Dr Graham Small and Dr Rosemary Lees. Prior to my master’s degree I had limited research experience and initially I was nervous about carrying out a desk-based project as being in a laboratory setting was much more in my comfort zone. However, through carrying out this project I have learnt numerous new skills which I will take away into my future career; from identifying the gaps in knowledge to establishing research questions, to analysing data sets and visually communicating research findings.

World Mosquito Day 2020 20th August 2020

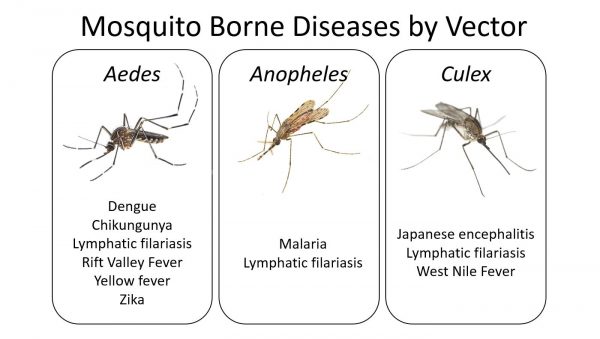

Today, the 20th of August 2020, is World Mosquito Day, an event that has been going since 1897 when Sir Ronald Ross declared this day soon after his discovery that female mosquitoes transmit malaria. The fact that mosquitoes transmit malaria is common knowledge nowadays, along with the discovery that many other diseases are spread by mosquitoes, including some familiar ones such as Dengue and Zika virus, and maybe some that are not so familiar such as Chikungunya, Yellow Fever, Eastern Equine Encephalitis, West Nile Virus and Rift Valley Fever.

You might expect that with the advancements of science and knowledge over the past century we would either have eliminated these diseases or at least be winning the fight. And there have been some remarkable achievements, deaths from malaria are now almost half of what they were 20 years ago. Unfortunately, the decline in malaria deaths has stalled over the past couple of years, Dengue has been rapidly increasing worldwide over the past 30 years and Yellow Fever, which has had an effective vaccine since the 1930’s, has been making a comeback. There are lots of reasons for the lack of progress but one of the main causes has been the development of insecticide resistance. Limited development of novel insecticides has meant existing mosquito control tools are becoming increasingly ineffective, leading to the resurgence and spread of many of the most dangerous mosquito vectors of disease, such as Anopheles gambiae and Aedes aegypti.

Now, in 2020, 123 years since the first World Mosquito Day, COVID-19 has upended our world and the knock-on effects for vector control could be disastrous. We are now at even greater risk with reduced travel and access to countries in need of support and resources. As you can imagine from our own experiences with COVID-19 the restriction of community-based mosquito control operations and an already stressed health system significantly increases the likelihood and impact of outbreaks of mosquito borne diseases. It is therefore essential to keep the emphasis on vector control otherwise an already bad situation could be made much worse. The World Health Organization (WHO) Global Technical Strategy for Malaria and the Global Vector Control Response have developed operational guidance for maintaining health services in the context of COVID-19 and has been urging countries to maintain their malaria services. There are currently over 700,000 deaths a year from mosquito borne diseases and we need to remain focused to avoid this increasing and adding another crisis on top of COVID-19.

Fortunately, there are several dedicated organisations working on ways to tackle mosquito borne diseases, including IVCC and its partners from industry and academia. Supported with funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, UNITAID, UKAid, USAID, The Global Fund, Australian Aid and, Swiss SDC, IVCC has been central to the development of novel insecticides to tackle insecticide resistance. In addition, IVCC has been helping to fund and develop innovative new tools, such as Attractive Targeted Sugar Baits (ATSB) and improved application equipment for residual spraying in and around households to add to and enhance the toolbox of control tools required to achieve the elimination of malaria and potentially other mosquito borne diseases. As part of the Australian government-supported Indo-Pacific Initiative (IPI), a package of bite prevention tools including spatial and topical repellents and insecticide treated clothing are being tested for malaria control. Much of the IPI work involves enhancing “Routes to Market” including a Market Access Landscape for the Indo-Pacific, providing a foundation for improved household and community access to life-saving vector control products.

Looking to the future we need to maintain and enhance the development of innovative and improved vector control tools to work towards a world free of mosquito borne diseases, just imagine how we might celebrate that momentous day. IVCC is focused on this mission and continually adapting its technical and strategic focus, as we all must, so that we may realise the full benefit of the knowledge gained over the past century.